Colorado Is Not a Rectangle—It Has 697 Sides

The Centennial State is technically a hexahectaenneacontakaiheptagon.

America loves its straight-line borders. The only U.S. state without one is Hawaii—for obvious reasons.

West of the Mississippi, states are bigger, emptier, and boxier than back east. From a distance, all seem to be made up of straight lines.

Only when you zoom in do you see their squiggly bits: the northeast corner of Kansas, for instance. Or Montana’s western border with Idaho that looks like a human face. Or Oklahoma’s southern border with Texas, meandering as it follows the Red River.

New Mexico comes tantalizingly close to having only straight-line borders. There’s that short stretch north of El Paso that would have been just 15 miles (24 kilometers) long if it were straight instead of wavy.

No, there are only three states whose borders are entirely made up of straight lines: Utah, which would have been a rectangle if Wyoming hadn’t bitten a chunk out of its northeastern corner; Wyoming itself; and Colorado.

Except that they aren’t. for two distinct reasons: because the earth is round, and because those 19th-century surveyors laying out state borders made mistakes.

Congress defined the borders of Colorado as a geospherical rectangle, stretching from 37°N to 41°N latitude, and from 25°W to 32°W longitude. While lines of latitude run in parallel circles that don’t meet, lines of longitude converge at the poles.

This means that Colorado’s longitudinal borders are slightly farther apart in the south. So if you’d look closely enough, the state resembles an isosceles trapezoid rather than a rectangle. Consequently, the state’s northern borderline is about 22 miles (35 kilometers) shorter than its southern one. The same goes, mutatis mutandis, for Wyoming.

That’s not where the story ends. There’s boundary delimitation: the theoretical description of a border, as described above. But what’s more relevant is boundary demarcation: surveying and marking out the border on the ground. Colorado entered the Union in 1876.

Only in 1879 did the first boundary survey team get around to translating Congress’s abstract into actual boundary markers. The official border would not be the delimited one, but the demarcated one. Unfortunately, 19th-century surveyors lacked satellites and other high-precision measurement tools.

Let’s not be too harsh: considering the size of the task and the limitation of their tools—magnetic compasses and metal chains—they did an incredible job. They had to stake straight lines irrespective of terrain, often through inhospitable land.

But yes, errors were made—and were in fact quite habitual. Take, for example, the 49th parallel, which for more than 1,200 miles forms the international border between the United States and Canada. Rather than being a straight line, it zigzags between the 912 boundary monuments established by successive teams of surveyors (the last ones in 1872–74). The markers deviate by as much as 575 feet north and 784 feet south of the actual parallel line.

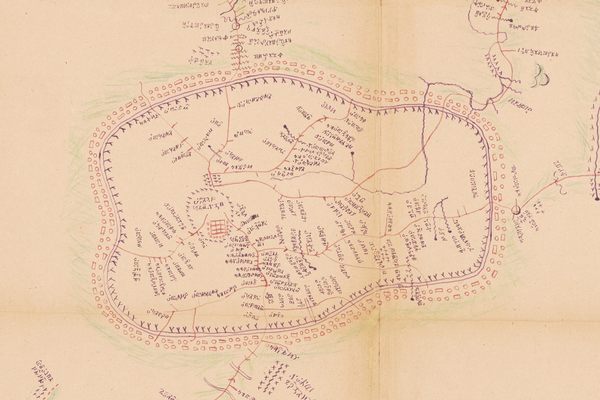

The same kind of thing happened when the first surveying teams went out to demarcate the Colorado border. These maps magnify some of the most egregious surveying inaccuracies, where the difference between the boundaries delineated by Congress and the border demarcated by the surveyors is greatest.

Four Corners (and Four More)

Located in a dusty, desolate corner of the desert, the Four Corners monument seems very far from the middle of anything. Yet this is the meeting point of four states: Utah, Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona. It is the only quadripoint in the United States. The monument’s exact location is at 36°59’56″N, 109°02’43″W.

However, it’s not where Congress had decreed the four states to meet. That point is about 560 feet (170 meters) northwest of the quadripoint’s current location, at 37°N, 109°02’48″W. Did you drive all the way through the desert to miss the actual point by a few hundred feet?

No, you didn’t: In 1925, the Supreme Court ruled that the borders as surveyed were the correct ones. But perhaps the original quadripoint deserves a small marker of its own, if only to provide the site with an extra attraction. Or why not go for three? Some sources say the original point deviates by 1,807 feet (551 meters).

The La Sal/Paradox Deviation

In 1879, a survey party marched north from Four Corners, placing markers at every mile. The surveyors eventually reached the Wyoming border, but not where they thought they’d end up. Later surveys, in 1885 and 1893, found out where the original surveyors had gone wrong, but by that time the border as surveyed had become the official one. Changing it would have required both Colorado and Utah to agree on a solution, and Congress to approve it.

The biggest error occurs just south of the road connecting La Sal, Utah to Paradox, Colorado. Across an eight-mile stretch, the surveyors strayed westward before regaining true north. The resulting deviation is 3860 feet (1.18 kilometers).

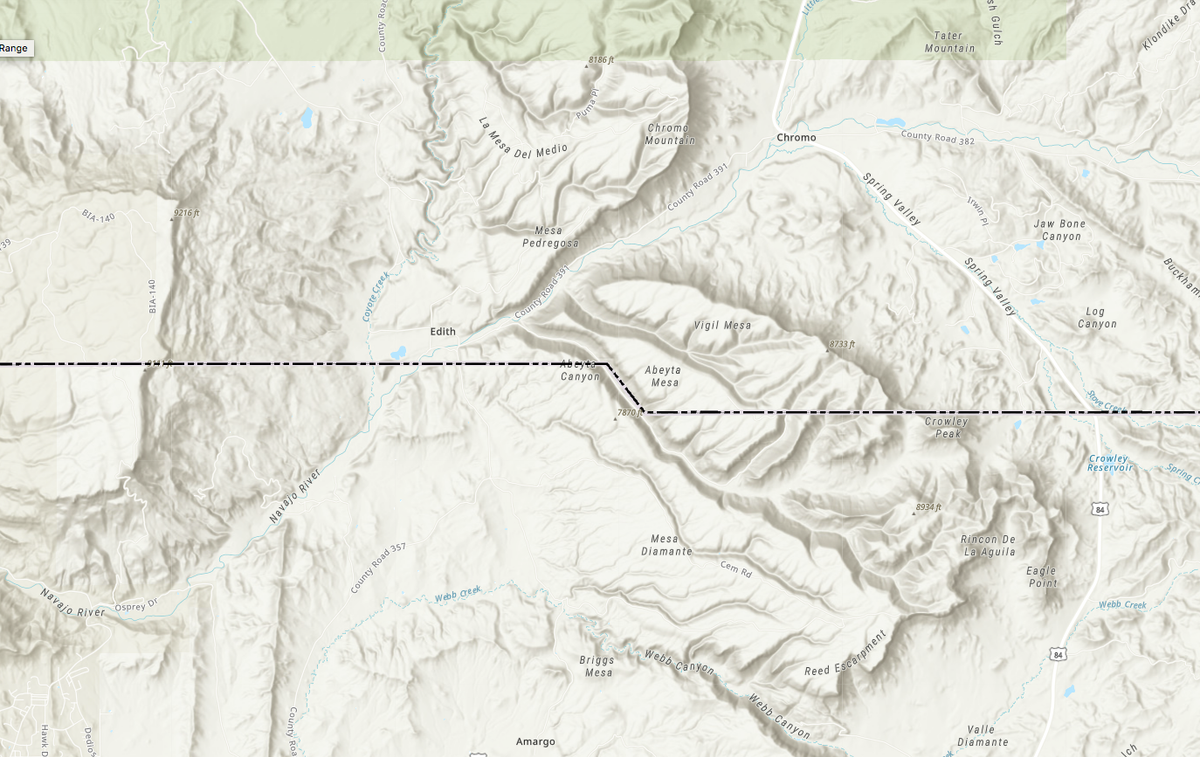

Things Go South After Edith

West to east, Colorado’s border with New Mexico starts out fairly straight. However, just east of Edith, the border swerves southeast for about 3,400 feet (1 kilometer) before resuming its course due east, now 2,820 feet (860 meters) farther south than before.

Why? It seems that for once, the surveyors have given in to the dictates of topography: the deviation follows a small valley oriented northwest-southeast.

Panhandling Into Oklahoma

Almost at the end of their surveying mission, it seems the party lost the plot again. In the last 53 miles (85 kilometers) before the border turns north, the stretch where Colorado rubs against Oklahoma, the line again swerves to the south, by as much as 1,770 feet (540 meters).

Don’t blame the terrain: Appropriately for a place so close to the Oklahoma Panhandle, it’s as flat as a pancake. Perhaps the surveyors were confused by the very featurelessness of the place.

Colorado Is a 697-Sider

These are just four of the biggest, most easily spotted surveying errors. In total, Colorado’s borders have hundreds twists and turns—most much smaller than the Big Four.

Accordingly, the state has not just four sides, but a total of 697 sides. So if Colorado is not a rectangle, what is it? Well, not a pentagon, (Greek for 5-sider), hexagon (6-sider), or a heptagon (7-sider), but a—hold on to something—hexahectaenneacontakaiheptagon (697-sider).

Don’t Get Your Hopes Up, Wyoming

With Colorado thoroughly disqualified to as one of America’s two truly rectangular states, does that leave Wyoming holding the crown all on its own? Nope. Turns out the surveyors who plotted the Equality State’s outline were just as fallible as the Colorado set. Interestingly, Wyoming’s deviations shown come in pairs, whereby the second ones seem to correct the deviation of the first ones.

So, while Wyoming is just as imperfect as Colorado, it does seem that at least it is better at admitting (and correcting) its mistakes than its southern neighbor.

This article originally appeared on Big Think, home of the brightest minds and biggest ideas of all time. Sign up for Big Think’s newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook